Dabadie on Dabadie

POSTED ON OCTOBER 3, 2016

The day before his 78th birthday (looking 20 years younger!), Jean-Loup Dabadie welcomes us to his apartment in the sixteenth arrondissement. A versatilly-gifted writer, Dabadie has authored magical screenplays for Claude Sautet and Yves Robert (of the famous diptych Pardon Mon Affaire - Pardon Mon Affaire, Too!), films whose impeccable timing and depth we are constantly rediscovering, but whose songs also float in the collective imagination (especially Ma préférence, written for Julien Clerc, "perhaps my best work," he says). Before a well-deserved tribute at the Lumière festival, he looks back on an impressive career, rattles off a few memories, and talks about his methods, with modesty. A great man.

How did you become a screenwriter?

Oh boy! The qustion is a bit cosmic! I've never earned my living by any other means than my pen. A drop of ink, a crumb of bread... When I was a literature student, I started writing sketches for Henri Salvador on Europe 1 radio, for a show called Salvadorissimo. It must have had a decent audience, because it got me noticed. I'd also published two novels with Editions du Seuil by the time I was twenty. Pierre Lazareff had read them - he reads everything! - and invited me into his group of newspapers, France-Soir, Candide, etc. I began writing news articles as well as humorous pieces.

So there I am, half-student, half-professional journalist, about to leave for military service. What follows - in no particular order because I'm no good with dates - are books, articles, sketches I send to Guy Bedos, a play, La Famille écarlate, which Pierre Brasseur is absolutely keen to bring to the stage… At the Théâtre de Paris, no less! Much too grandioise for me! With Françoise Rosay, Rosy Varte, big names...

Serge Reggiani, who had read my play, calls me, "Could you write song lyrics for me?" I protest, "But sir, I'm not sure I can. I've never done that." "It's because you've never written lyrics that I came to you." And so I write the first song of my life, Le Petit Garçon. A huge hit. After that, it's one song after another, for Michel Polnareff, for Julien Clerc, and so on.

Well then what about the screenplays?

Jean Poiret and Michel Serrault are starring in an English play I had very freely adapted for them, La Vison voyageur (original title: Not now, darling). It just so happens that Mrs. Sautet brings her husband to the theater. Claude is crying with laughter at the play, he was a great laugher. We then meet at a producer's, Francis Cosne, who made lighthearted Parisian films, sometimes with Brigitte Bardot, often staged by the delightful Michel Boisrond, an elegant and charming man. He brings Claude and I together, because Boisrond wants to direct a thriller based on a Serie Noire and asks us to write the adaptation. We start working, we can't manage to do it, but we become friends. I fall under the spell of this warm man who laughs, cries, is moved to tears when we talk of family, children.

Another friend of mine, Paul Guimard, had written a novel, The Things of Life. His publisher had shown several producers the book, to repeated refusals. We get together with Paul on vacation in Brittany. He says: "Jean-Loup, would you write an adaptation? "I come out with a first draft of the script. My agent sends it to relatively well-known filmmakers- I won't name names. They reject me right off the bat. One even writes a note: "I read the first pages. Luckily my wastebasket was closeby so I could toss it in directly." So I reach out to Claude Sautet, saying, "You know everybody, I know no one. Who can I have read these twenty-four pages?" Claude tells me to leave it under his doormat at 5 avenue des Gobelins, promising to read it over the weekend. On Monday, he calls me: "Pal! - his favorite way of addressing people - I want to come back to the cinema. I'll direct the film." He had given up directing since The Dictator's Guns five years earlier.

What do you think convinced him?

He felt a jolt of emotion. He already had a vision of the film he could make. He was probably already imagining how to shoot the car accident. So we get to work, using to a method I often used later: I write alone, then every other day we'd read and make corrections together. Claude Sautet had great quality: he was a great reader. He read all the roles magnificently. Claude even read the female roles with extraordinary intensity. When they told me, after César & Rosalie "Ah yes, César is Sautet," I replied, "But Rosalie, too, is Claude!" When the story was being written, he went into a state of fervor, of incredible emotions. Jean-Paul Rappeneau is also a great reader; he reads with a wonderful cadence - you can picture the scenes before they're filmed.

Did your different past professions serve as an asset in writing screenplays?

Journalism, certainly: the famous "where, when, how?" It leads to requirements that are essential for a script. When I turned in my first articles to Paris-Presse, my editors said, okay, they're very well written, but who is it about? When is it taking place?" I retained the lesson. I remember an article I was asked to write on the assassination of Kennedy, I knew I had to quickly describe the scene: "Jackie, dressed in her little pink suit, gets into the car," etc. But I can also answer your question another way: being a journalist has taught me to build my scripts, write my dialogues, and also compose songs, write plays for the theater. Strip the dialogue down and remove everything superfluous- parasites of language. Write as simply as possible, thinking about the story, its characters and the audience too. But at the same time, write without complacency, without a technique.

What scene are you most proud of?

That's impossible to answer. I can't be proud of myself as a writer when I'm watching a scene... I can tell myself that it's not badly written, but the acting and directing are essential. So what can I say? The scene in César & Rosalie where they are on the beach in Sète: David (Sami Frey) and Rosalie (Romy Schneider) are having a picnic, when along comes the powerful car of Monsieur Jourdain, our César, our Yves Montand, with his suit, his tie. "What a wonderful scene in the country! The weather is horrible in Paris! " He has reconquered Rosalie, you can see it in her eyes...

It was a scene, like a few others, that had sparked one of Claude Sautet's legendary rages. In order to wake up the crew, a bit sleepy under the sun of Sète, he yelled, "I can't believe this! I didn't hear a word of what Sami said! I can't hear a thing !" The sound engineer cautiously approached him and said, "But Sami deson't have any lines in this part." So, yes, it's a moment I really like- because of the genius of Claude, because of the actors' talent, and I guess I knew more or less how to make my writing fit in there somewhere...

What about Marthe Villalonga, storming onto the tennis court in Pardon Mon Affaire?

Sure ... I like lots of scenes in both films by Yves Robert. I laughed hard at seeing this scene, even though I'm generally not fond of watching films I've written... I did a good job, but it was Yves Robert who put it all together so well with his expert directing. The way Marthe Villalonga arrives with her vulgar fur coat, while Yves films all the other courts at the same time... It works out really well!

When creating a script, do you make staging notes?

Yes, I can't help making staging notes; then the directors can do what they want. The same goes for the actors: "She puts her hand over her mouth, realizing that..." One day on The Things of Life, I remember a scene Sautet was happy with. Romy and Piccoli had just quarrelled and he decides to leave. And I had described the face of Romy in three parts: she looks at him, she looks down, she tilts her head. And that's in the film!

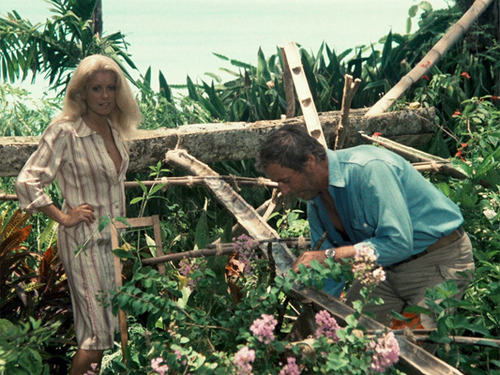

In Le Sauvage by Jean-Paul Rappeneau, there's the "magnificent garden" of Yves Montand, filmed partially in the Bahamas, partially in St. Tropez - that's the acrobatics of the cinema for you! I wrote a page and a half of description: the plump round tomatoes, the sound of flowing water, etc. It's just for honor that I write this, because when the scene actually exists, who knows what the garden will look like, which vegetables we'll have, etc. Jean-Paul told me, "Even if we don't film this, it's important that the crew understand it; it sets the mood..." This is part of the humble duty of the screenwriter. You're not the director, but you have to get as close as possible to the image and the sound… And at the end of the day, the filmmaker has the final say.

Some of your scripts show influences of Italian comedy...

The writers who attracted me to the cinema were the great Italians. Age and Scarpelli [Agenore Incrocci and Furio Scarpelli signed all their screenplays Age & Scarpelli. - Ed. note], Suso Cecchi d'Amico, Ettore Scola. One year, they graciously presented me with an award, for best foreign author. I liked their incredible spirit of brotherhood; they were always together. Cecchi d'Amico was the queen mother, she introduced the others. "Here's Scarpelli, our Mr. handsome!" It's true that he was a good-looking guy! Yes, I loved We All Loved Each Other So Much. For me, so keen on team sports, I saw that these people loved working together. They told me: "Sometimes, one of us has an idea. So we go see him, eat pasta, talk..." I would have loved to write in a group like this.

Yves Robert's films seem to be the "comedy" flipside of Sautet's dramas...

I'll answer you by quoting novelist and screenwriter Pascal Jardin, a great friend of Claude Sautet's. In an interview, he saod, "I'll explain Jean-Loup to you. You put the films he writes in a shaker, you shake up his scripts and dialogues. If you pour it out one side, you have the dramatic side, the films of Claude Sautet. If you pour it out the other side, you'll have the comedies of Yves Robert." That's exactly right. One thing to add: in real life, Yves Robert's best friend was Claude Sautet, and Claude Sautet's best friend was Yves Robert...

Seeing Vincent, François, Paul and the Others again, one is surprised that the dialogues contain bits and pieces of everyday speech... was it written that way ?

There are two methods of writing that I often used: First, the voiceover. Jean Rochefort's distant voiceover in Pardon Mon Affaire. Or Romy Schneider's letter to Sami Frey, which people often talk to me about, in César & Rosalie. Another technique that I liked a lot was inspired by Yves Montand: incomplete sentences. And I can tell you that it is very specific every time. A line I'm proud of is the last one in Vincent, François, Paul and the Others. They're about to cross the street, they're at a busy intersection, and Montand hasn't given up hope that Stéphane Audran (who plays his wife) will return to him. But we we know that it's pointless, it's over. He declares, "And Catherine, she could come back to me. You never know. In life." Freeze frame. The end. I really like that!

Do you write a specific way for certain actors?

I have a passion for actors. Sometimes you try to write, you pratically kill yourself to get to the end of a line; you try to get the words out with the emotion or humor you're looking for. And then you stop, thinking "I can't do any better than that." Months later, during the rushes or screenings, you'll be watching Isabelle Adjani or Catherine Deneuve or Michel Piccoli and the lines come out of their mouths as if they've just invented the words. It's a highly personal and indescribable feeling.

But to answer your question, yes, Romy Schneider, for example, in A Simple Story- I have often heard that Claude Sautet was right not to cut the line where she makes a mistake... It's a scene where she's in one of our cafes with Bruno Cremer, it's raining outside and the windows are all fogged up. They've had several drinks, she looks a bit tipsy. Cremer asks her, "How 'bout another drink?" She replies, "No, that's okay. I too much drank. Oh no - to speak correctly, I should say, 'I drank too much.'" Well those exact lines were written for Romy Schneider, note for note. She carries it off divinely, and everyone thinks she's making a mistake.

Have you ever considered yourself a sociologist of 1970s France?

That is the work of journalists, film historians, to find hidden patterns. It reminds me of being at the Sorbonne, when we were studying Baudelaire, the profs would say, if this particular word is in this particular place, it's because the author considered this or that... I said to myself, no… maybe after the fact we can analyze it to death, but that's not the way one writes - the word just comes or it doesn't. It annoyed me and Sautet for example when we were told we had "described the France of Pompidou to a tee." But we weren't trying to describe Pompidou's France! Claude Sautet said to me, especially when he refused certain ideas of mine, "It's good, but I don't know how I'll do it. I can only film what I know." Hence, the tables of family lunches, the women who push you to question yourself, the buddies, etc.