Carné, post-Prévert

PostED on october 4, 2016 AT 3PM

And one day, they went their separate ways... In the wake of WWII, Jacques Prévert and Marcel Carné are not yet 50. Over the previous decade, they had churned out half a dozen masterpieces, landmarks in the history of French cinema. They invented a new form, "poetic realism," a questionable expression. One could describe their films as full of the fatalism and fantasy that permeated the arts of the 1930s - exemplified in the theater, in plays by Ferenc Molnár or Odon Von Horvath. The specter of war on the horizon explained the pessimism. But war broke out, and ended. And suddenly, Roberto Rossellini is filming occupied Rome and Berlin in ruins, almost live. The tune has decidedly changed...

Cracks begin to show in the Carné-Prévert duo after the (unjustified) relative failure of Gates of the Night (1946). Carné is criticized for reconstituting the Barbès-Rochechouart metro station in the studios of Billancourt - deemed too costly. The film was doubtless overly faithful to the aesthetic ideals of the past. The following year, the filming of La Fleur de l’âge (with Anouk Aimée, Serge Reggiani and Arletty in much-heralded return), still served by a Jacques Prévert script, is interrupted, and the project abandoned. The poet would write dialogue again, almost incognito, for La Marie du Port (1950), penning perhaps the most "picturesque," less authentic passages of the fine adaptation of Simenon's work. Working without Prévert, Carné proves that, keeping to a reasonable budget, he is capable of filming a port without shadows and characters who don't meet their (tragic) fate on every street corner.

From this point forward, Marcel can exist without Jacques. Carné will alternate novelistic and technically ambitious works (becoming perhaps, the most skilled French "filmmaker" of the era) with more personal films (often a result of the inability to gain funding for a bigger project). In the first category, a free adaptation - transposed to Lyon - of The Adultress (1953) by Emile Zola, is a milestone, not only due to to the performance of Simone Signoret, off the heels of Casque d’or. In the second, Carné incessantly returns to youth, to the "invention" of the postwar period he finds fascinating and alluring. More than a mere desire to keep up with the times, it reflects a taste that is acutely personal, nearly obsessive.

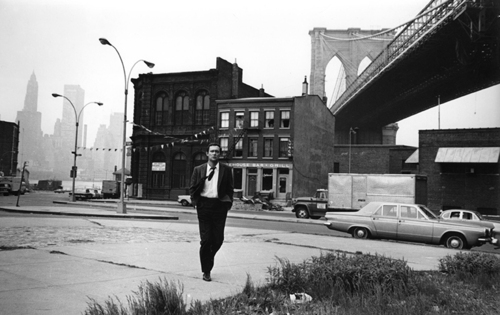

Youthful Sinners (1958), which needs rehabilitation for its "pre-punk" disappointment, curiously echoes Rendezvous in July by Jacques Becker. The latter, released nearly a decade earlier, depicts idealistic youngsters of the Liberation who have become into old teenagers, sinking into sad hedonism. Carné captures the psyche of an era, but also its places (jukebox diners) and pastimes (the "Game of truth" becomes a must-have item in the months following the film's release). This new appetite for observation also characterizes Three Rooms in Manhattan (1965). Based once again on a Simenon work, the filmmaker lays out his own vision of the New York metropolis - with the interior scenes filmed in Paris, using furniture directly imported from the States. It hampers him a bit, compared to yesteryear, when the studio provided him with complete freedom. Here's a hypothesis to ponder: consider the trajectory of Marcel Carné as that of someone who gradually breaks free, beyond the cinematic perfection manufactured in the studio, and finds his own voice. Then he makes that voice heard, like it or not.

Adrien Dufourquet